In addition to the psychiatric disorders mentioned above, people with I/DD also may experience behavioral issues that impair their ability to do well in family, educational, and employment settings. Without rising to the level of a diagnosable disorder, anxiety, mood, or stress-related difficulties may disrupt the person’s family or social relationships. In particular, emotion dysregulation may lead to school avoidance/refusal/academic difficulties, as well as causing distress to the individual. Poor self-esteem may reduce the person’s quality of life. CBT can also support adaptive coping responses to stressors and play a part in social skills training, both in responding to and interacting with others and in understanding and predicting their behavior.

"Emotion Dysregulation"

"Emotion regulation is a broad concept that refers to a set of interrelated processes that drive which emotions an individual has, and how he or she experiences and expresses them. It encompasses a wide array of physiological responses, subjective cognitive and affective experiences, and behaviours that may be automatic, unconscious, and effortless or controlled, conscious, and effortful, yet all serve a common function: supporting adaptive behaviour. Emotion regulation processes therefore deal with modifying one’s emotional reactions to facilitate advantageous outcomes in a particular situation. Emotion dysregulation occurs when these processes are impaired and fail to achieve this goal." (Ryckaert, Kuntsi, & Asherson, 2018)

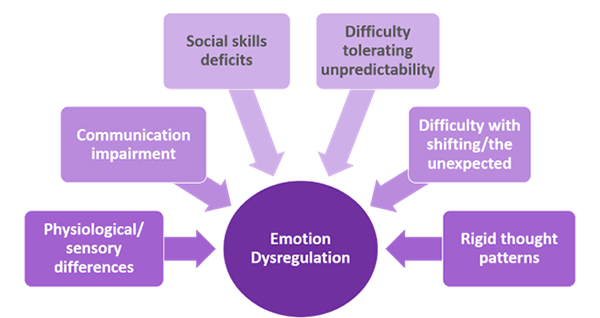

Factor Contributing to Emotion Dysregulation in People with I/DD

Accommodations would likely include modifications the practitioner would make to work with young people, rather than adults. These are:

- including a parent/caregiver to assist with coaching and skills practice outside the session

- using reinforcement and motivating factors to encourage participation

- using concrete examples to teach therapeutic tools

- tailoring teaching strategies to the person’s developmental level

- incorporating skill building/lessons into developmentally appropriate, regular activities and routines.

Additionally, people with I/DD may be more likely to exhibit cognitive tendencies linked to anxiety/emotion dysregulation. For example, people with I/DD often demand consistency and certainty, have perseverative and/or inflexible thinking, and have difficulty recognizing emotions and converting thoughts about them to speech. These and other tendencies may require changes in how the practitioner presents the therapy.

To determine if CBT is likely to be effective and to plan for additional accommodations, the practitioner should make an initial assessment to understand more about the individual’s challenges and developmental profile. Because people with I/DD are more likely to have a scattered cognitive or learning profile, it can be helpful to review results of previous assessments to better understand how to tailor instruction and coaching. For example, individuals who are challenged with verbal reasoning would benefit from more concrete verbal explanations with use of visual aids. Additionally, individuals with challenges in processing and working memory may benefit from extended processing time when reviewing topics and from visual aids to recall important information or concepts. Also, gathering information at the onset of treatment about strengths, interest areas, and key caregivers to involve in therapy can help optimize participation in treatment and attainment of skills.

Instructional Approach

- Bolster abstract concepts with more concrete language and approaches (e.g., use visual supports, scripts, and structured/hands-on activities).

- Include multimodal teaching strategies including modeling, role-playing, video modeling, and repeated practice (teaching a skill through multiple modalities).

- Provide executive functioning support when needed by chunking information, providing visual organizers for planning, providing breaks to help with sustaining attention, and using visual reminders to recall information.

- Consider using activities and illustrations to make abstract emotional and cognitive topics more easily understood.

- Plan for shorter, more frequent therapy sessions or a longer course of treatment, as needed, to teach skills at an adequate pace and for client to retain and adopt skills.

Behavior Support and Behavioral Skills Practice

- Use of positive behavior supports can enhance participation and skills practice in sessions. The practitioner might:

- incorporate the person’s special interests in content and use them to reinforce skills practice

- use positive behavior support strategies to redirect challenging behavior and encourage other expected behaviors during the session

- use environmental supports such as visual schedules, checklists, and timers to create appropriate structure and routine during the session.

Behavioral skills practice may focus on building adaptive coping skills such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, meditation, or other relaxation methods to reduce anxiety and forestall maladaptive behavior. Concrete tools and visual supports can be helpful for developing and practicing coping skills, as can video modeling. Use of objects and sensory materials can also serve as a more concrete calming or redirection strategy. It is important to partner with parents/caregivers to identify proactive relaxation and sensory routines for the person to implement throughout the week.

Coaching Parents/Caregivers

An important part of treatment includes equipping parents/caregivers with strategies for preventing or responding to emotion dysregulation and agitation. Their participation can help the person with I/DD generalize and practice emotion regulation and coping skills between therapy sessions. It is important to involve parents/caregivers during the sessions to teach them how to model skills and provide reminders and reinforcement for using them, and they can report on progress and barriers between sessions. Here is an example of materials that could be shared with parents/caregivers about strategies for managing emotional dysregulation caused by anxiety.

| Preventive Strategies | Responsive Strategies |

|---|---|

|

|

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation focuses on teaching foundational skills related to recognizing and communicating about emotions and managing those which produce maladaptive behavior.

Given the difficulty that many people with I/DD have in recognizing emotions, the practitioner may use any of a number of aids to help clients identify them. There are commercial products with personifications of emotions (e.g., http://www.worrywoos.com/), but the recent ubiquity of emojis may also provide images that can be used for materials specifically tailored to the person.

Several other types of tools may assist people with understanding ranges of emotions (e.g. “The Incredible 5-Point Scale,” https://www.5pointscale.com/) and communicating them to others. Others, such as the “Zones of Regulation” (http://zonesofregulation.com/) include visuals and tools to assist with communicating and monitoring emotions and behaviors, while others still illustrate the relationship between emotions and positive or negative outcomes in social situations (https://www.socialthinking.com/).

Note: Mention of these products should not be construed as formal endorsement by NCDMH/DD/SAS or the School of Social Work at UNC-Chapel Hill. These are provided as examples only, and similar products not shown may also be helpful to the practitioner and client.

Thought Monitoring and Cognitive Restructuring

One of the key components of CBT is identifying and working to change thought patterns. Thought monitoring involves paying attention to automatic and potentially maladaptive patterns, while cognitive restructuring focuses on challenging and changing those patterns by replacing them with more adaptive thoughts that are typically more flexible, realistic, and optimistic. Both often involve collecting data to identify and monitor patterns by identifying problematic situations, the automatic/immediate thoughts and associated moods and emotions they evoke, evidence supporting and denying initial thoughts, possible alternative thoughts, and subsequent moods and emotional responses. Because thought monitoring can be an abstract concept, it is often helpful to include visual supports to illustrate the relationships between context, thoughts, feelings, actions, and results, and to identify alternatives that might change negative results to more positive ones. Here is an example of a tool for monitoring those relationships (a free download from https://www.getselfhelp.co.uk/docs/ThoughtRecordSheetPictorial.pdf).

Practitioners will be familiar with typical maladaptive thought patterns—cognitive distortions such as black-and-white thinking, catastrophizing, overgeneralization, mind-reading, etc.—and ways to help the person challenge them.

Complementary Skill Building

CBT can be effectively used to address anxiety, mood-related, or other psychiatric concerns, but it is often helpful in building the person’s adaptive skills in understanding and predicting the behavior of others by considering how their behavior might be influenced by context and mood. Because many people with I/DD have difficulty interpreting nonverbal communication, this can help them function more effectively at home, at leisure/play, and in educational or employment settings. For example, a teaching moment might occur when walking down a crowded city sidewalk, and using that experience to explain why most people aren’t interested in stopping to say hello in response to your greeting. That does not mean that people don’t like you, but rather that they have places to go themselves and are just trying to get to their destination quickly.

Exposure

Because people with I/DD may have idiosyncratic, aversive responses to some stimuli, reducing the ones that impair functioning may be a goal of CBT. Exposure is one possible method. When it is used, it is essential to plan and select appropriate strategies. Flooding and gradual extinction procedures are two that may be used to treat anxiety and avoidant behavior patterns. Flooding consists of confronting the person with their object of fear in a controlled situation, while gradual extinction involves identifying a hierarchy of fears and helping the person to face them one at a time as they practice coping strategies, until the initial fear response is extinguished. This figure provides an example. The practitioner and parents/caregivers would pair exposures with relaxation strategies and establish rewards for accomplishing each step.

A typical CBT session might involve these activities, although session formats will vary according to individual needs and goals. Practitioners will use concrete examples related to the person’s interests, tailor teaching strategies to the person’s level of development, and reinforce

- emotion-monitoring and/or thought-monitoring practice

- cognitive restructuring and behavioral coping skills practice

- behavioral activities (e.g., exposure exercise, behavioral activation, adaptive behavior practice)

- parent/caregiver training to assist with coaching and skills practice outside of session

- individual homework.