Trauma

Trauma occurs when an individual either experiences or witnesses a real or perceived threat to their emotional and/or physical well-being and the intensity of this experience negatively impacts the individual. Trauma does not necessarily have to be a particular event. It can also result from chronic neglect of basic needs, whether emotional or physical.

People who have persistent emotional distress that interferes with their well-being and ability to function after the trauma has ended may be suffering from traumatic stress. Traumatic stress is based on the individual’s response to an event or situation, so not everyone who experiences a potentially traumatic event or situation develops trauma-related symptoms. That said, prolonged or chronic exposure to trauma and stress produces the most severe and lasting effects.

Children with I/DD or mental health disorders are at substantially higher risk of experiencing traumatic situations as compared to typically developing children. In general, children with I/DD or mental health disorders are:

- 2 times more likely to experience physical and sexual abuse

- 4 times more likely to be victim of a crime

- 2 times more likely to experience emotional neglect

- 3 times more likely to be exposed to domestic violence

- 1.5 to 2 times more likely to be bullied.

This increased risk may be related to the need for intensive care and the likelihood of having challenging behaviors.

Trauma from victimization

The higher incidence of early puberty, multiple caregivers providing intimate care, communication barriers, learning problems, and residential care can increase vulnerability to sexual abuse.

Externalizing behavior, which can be verbal and physical aggression as well as self-injury, is more common among people with I/DD, particularly among those who have limited ability to communicate in conventional ways. While aggressive behavior is associated with a higher risk for physical abuse in all populations, the cognitive and developmental delays experienced by children with I/DD make them more vulnerable to exploitation and manipulation than their peers. Stress on families and caregivers can increase the risk of maltreatment or neglect. Communication difficulties may prevent children with I/DD from reporting abusive experiences or bullying by peers.

Trauma from medical care

Children with I/DD who have complex medical needs may experience trauma through the health care system. Diagnosis and treatment can be a source of trauma. Given the increased complex medical needs of children with I/DD, they are at an increased risk for undergoing medical procedures, often repetitively or over months or years. Communication difficulties may increase children’s level of distress if they do not understand the reason for or sequence of procedures (consider how noisy and cramped an MRI machine is or how potentially uncomfortable blood draws, catheterizations or dental procedures may be). Individual sensory differences and aversions and visual or hearing impairments may increase distress. Anxiety and unease can lead to agitation, aggression, and/or self-injurious behaviors, yet few medical settings have trained personnel or resources to provide support or alternative methods of communication.

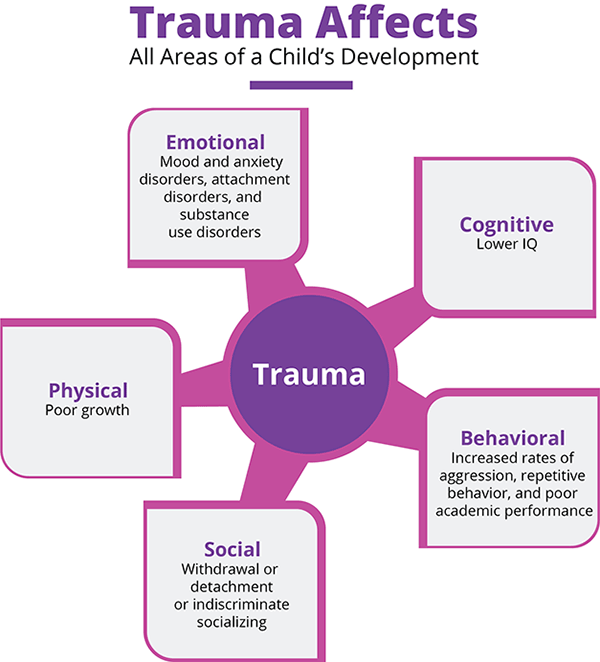

Traumatic stress can lead to changes in learning (language, cognitive, and social emotional skills), behavior (adaptive and maladaptive), and physiology (chronically activated stress response).

The National Institute of Mental Health points out that there may be a gap of weeks or months between the traumatic event and symptoms of traumatic stress. Here are the typical symptoms by age group among typically developing children.

| Age 5 and Under | Ages 6 to 11 | Ages 12 to 17 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| These symptoms are taken from the National Institute of Mental Health, Helping Children and Adolescents Cope with Violence and Disaster | ||

There are many complicating factors in recognizing trauma in children with I/DD.

- Diagnostic overshadowing—that is, attributing behavior to I/DD rather than investigating other causes—may keep professionals from recognizing the effects of trauma. Some behaviors that are symptoms of traumatic stress are also common among children with I/DD or associated with the reason for their condition, making it difficult to find the cause of the behavior. For example, people with Fragile X Syndrome have a higher rate of anxiety than the typical population, so anxiety-producing trauma may be missed.

- Co-occurring medical or mental health issues may cloud recognition.

- Differences in sensory perceptions among children with I/DD may lead them to respond differently to trauma.

- Communication challenges may make it difficult for children with I/DD to report traumatic events or conditions, and families and care providers may not understand what they wish to communicate.

- Children with I/DD often have fewer resources to lessen the effect of trauma. For example, neurological deficits may reduce their flexibility to respond or to participate effectively in psychological interventions that promote recovery. They may have smaller systems of social support, and they may experience social rejection and stigmatization.

Given all this, how does one recognize trauma in children with I/DD?

Looking at the list of symptoms, you may notice behaviors that are typical of children with I/DD and that overlap with symptoms of traumatic stress. So, how would you or a care provider distinguish traumatic stress? The key is a change from the child’s usual behavior. There are some additional symptoms you may notice, and it is helpful to remember that developmental delays may make older children respond in ways that are typical of younger children. Some of the additional symptoms include:

The trauma-screening tools often require adaptations to be effective with people with I/DD. To gather information, practitioners may need to involve a wide range of informants in the assessment process. Screening of young children might include day care providers, parents, and babysitters. For school-age children, reports from teachers, special education staff, and interpreters might be helpful. For older children and adults, residential staff, spouses, and personal aides might provide information. Additionally, these informants may need psychoeducation about the signs or symptoms of trauma and abuse among people with I/DD.

Interviewing children or adults may require the practitioner to make adaptations such as:

- slowing the pace of speech and questioning

- simplifying language and avoiding compound statements

- presenting concepts one at a time

- using concrete examples (e.g., pictures, dolls)

- using questions that build on the person’s strengths

- using an interpreter or someone more aware of the person’s communication style or adapting to the person’s method of communication with assistive devices or alternative communication methods.

When screening suggests that the person is suffering from trauma, a comprehensive trauma mental health assessment should be conducted by a mental health provider who is dually trained in I/DD and mental health. This assessment may occur over multiple sessions and should include an in-depth exploration of the event’s severity, the impact of the event(s), the current trauma-related symptoms, and functional impairment. The provider should conduct one or more clinical interviews, use objective measures including behavioral observations, make collateral contacts with family, caseworkers, or teachers, and use the assessment finding to drive treatment planning.

Primary care providers who are responding to concerns about trauma can provide other positive and strength-based responses.

- Providers should recognize and emphasize the strengths of the family or the individual’s support system. Practitioners should take time to listen to you and other caregivers, consider your questions, concerns, and challenges, as well as providing psychoeducation about healing and protective environments. Likewise, it will be important for providers to ask about siblings, housemates, or others affected by the trauma. You and other caregivers often may need assistance in accessing resources for support, treatment, and respite care.

- Providers should recognize that you and other caregivers may benefit from referral to support groups to help you cope and effectively address challenging or disruptive behaviors such as panic attacks, frequent masturbation, self-injury, and lack of socialization, which can be very difficult to manage without on-going support.

- Providers should give you and your family hope. Families need to know that recovery from trauma is possible. Some ways to instill hope are to educate parents and caregivers on how to provide a sense of safety and consistency; listen to patients, parents, and caregivers and validate what happened; and provide the family with resources and assist them in accessing those services.

Psychosocial Interventions

Treatment of trauma and traumatic stress for people with I/DD is similar to approaches used for neurotypical individuals, but these interventions require adaptation to the person’s developmental and language ability. Here are the most commonly used interventions.

- Trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT), the treatment of choice, if the person is cognitively able to participate,

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT),

- Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing (EMDR),

- Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT),

- Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP),

- Positive Identity Development

For additional information on interventions, see NCTSN’s descriptions at https://www.nctsn.org/treatments-and-practices/trauma-treatments/interventions, remembering that these are tailored to neurotypical children.

When the trauma stems from bullying, it is important for parents, caregivers, and providers to work with school personnel to protect the child from harm.

Medication

Some people may benefit from medications for anxiety and depression. When psychosocial interventions alone are insufficient, an evaluation by a qualified professional may be appropriate. Prescribing psychotropic medications for people with I/DD is complicated, so you should be sure to find a health care professional with expertise in treating people with I/DD.

Out of Home Care

While removal from home is sometimes required to provide safety, people with I/DD may experience additional trauma from such a change. In typically developing children, such changes can precipitate disruption in sleep patterns, withdrawal, anxiety, and dissociative behavior. In children with I/DD, diagnostic overshadowing might mask the child’s reaction to change. Disrupted relationships can derail learning of self-regulation skills and hinder the child’s developmental progress. The child will need additional explanation and time to understand the reason for the change in living situation, as well as clear expectations for returning home. Plans should be in place to maintain the continuity of medical and behavioral care should a child be removed from home.

A reminder: North Carolina law requires anyone who suspects abuse, neglect, or exploitation of a child or disabled adult (over age 18) to report it to the county department of social services. See the online directory of DSSs at https://www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/social-services/local-dss-directory.

Three symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder are particularly common among people with I/DD:

- remembering and re-experiencing the trauma,

- avoidance of situations that lead to remembering/re-experiencing, and

- hyperarousal—fight or flight behavior—which can lead to aggression and property destruction.

All of these can produce difficult behaviors if the person cannot find a way to recover from the trauma. Dr. Karyn Harvey (2014) suggests that to recover, people with I/DD need to feel safe from repeated exposure to trauma, to have supportive social connections (which many people with I/DD lack), and to have real choice about important aspects of their lives (also frequently lacking), which can provide them with a sense of hope. Because the experience of trauma is so common among people with I/DD, practitioners and families need to understand its effects and work to support recovery.

——. (2011). Birth parents with trauma histories and the child welfare system: A guide for Child Welfare Staff. https://www.nctsn.org/resources/birth-parents-trauma-histories-and-child-welfare-system-guide-child-welfare-staff

——. (2012). The 12 core concepts: Concepts for understanding traumatic stress responses in children and families. https://www.nctsn.org/resources/12-core-concepts-concepts-understanding-traumatic-stress-responses-children-and-families

——. (2015). The road to recovery: Supporting children with intellectual and developmental disabilities who have experienced trauma. https://www.nctsn.org/resources/road-recovery-supporting-children-intellectual-and-developmental-disabilities-who-have

See also their Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress Toolkit for Health Care Providers, https://www.nctsn.org/resources/pediatric-medical-traumatic-stress-toolkit-health-care-providers.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/helping-children-and-adolescents-cope-with-disasters-and-other-traumatic-events