Crisis Response for Families

In general, a person’s behavior is considered a crisis under the following circumstances:

- The person’s aggression or agitation has escalated to a point where the person, or others in the person’s immediate vicinity, are at risk of physical harm;

- The person is demonstrating new behaviors that could indicate mania, delusions, hallucinations, or impaired judgement;

- The person is demonstrating suicidal behavior or expressing suicidal thoughts that are new or unusual for the person.

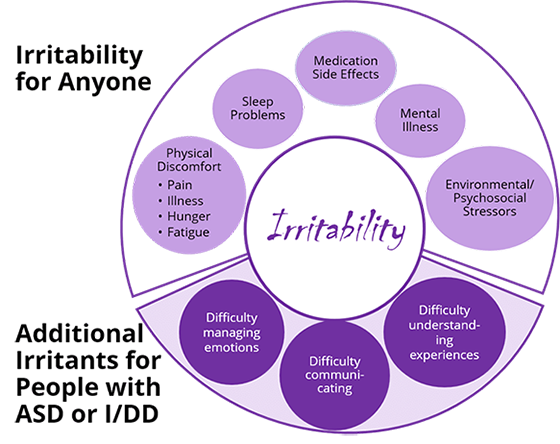

First, Let’s Discuss "Irritability"

Most behavioral crises among people with I/DD are characterized by aggression or extreme agitation. Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) often have heightened sensitivity to physical and environmental stimuli, which can magnify a tendency to exhibit uncontrolled anger or aggression. Up to 30% of children with ASD have symptoms of "irritability," including aggression (25%), severe tantrums (30%), and deliberate self-injurious behavior (16%). This is very problematic in young children and particularly dangerous in adolescence, especially among boys. Let's look first at irritability and its causes.

Assessing "Irritability"

Crises associated with explosive behavior and agitation are complex to sort out and often result from more than one source. Remembering that the person may have difficulty communicating what the problem is, the place to start is with the most common medical drivers of irritability:

- constipation/encopresis (the effect of which is often underestimated)

- pain

- gastrointestinal

- dental

- secondary to infections (e.g., urinary tract or respiratory)

- premenstrual

- medication side effects

- psychostimulants (common culprit)

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (common culprit)

Other potential situational or environmental causes of the difficult behavior should also be considered: - Does the person have difficulty with transitions?

- Do the episodes occur around mealtimes or bed time?

Irritability can escalate in severity to the point of crisis in two ways.

- Severe mood changes and agitation: Yelling, flopping, kicking, screaming, prolonged tantrums, bolting away, and low tolerance for frustration.

- Aggressive behaviors directed at self or others

- Biting, spitting, kicking, hitting, throwing things

- Self-injury such as head banging, wrist biting, slapping, scratching self

- Destroying property

The vast majority of crises with aggression and agitation are "acute on chronic," meaning a recent worsening of longstanding challenges involving explosive behavior. Caregivers, and especially families, may have a raised threshold for what constitutes an emergency because of their chronic exposure to very challenging behaviors. Families may be fearful of calling 911 for help and also about potential negative experiences in the emergency room. Most explosive episodes will remit in minutes to hours, and having extra people in the immediate area often maintains safety in the meantime. The need for transportation to the ED is rare, but there are important exceptions.

Mental disorders are more common among children who have I/DD than among the general population—from 30 to 50%, compared to 8 to 18% among neurotypical children. That said, behavioral problems commonly observed among people with I/DD may or may not indicate a co-occurring psychiatric disorder. Diagnosing mental disorders is challenging, and the goal is to strike a balance between identifying appropriate avenues for needed help while avoiding additional mental health diagnosis that may be inappropriate at best.

Overlapping Symptoms

The great difficulty in identifying mental disorders among people with I/DD is that it is often difficult to decide which disorder is responsible for any given symptom. For example, a person with I/DD whose symptoms include poor self-care or weight loss might also have Depressive Disorder or Anxiety. A person with ASD who has repetitive behavior might also have Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. A child diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder might experience a manic episode related to Bipolar Disorder in his teens. Once considered to be rare diagnoses among people with I/DD, primary care providers are increasingly encountering patients with these disorders, particularly among those with mild ASD and most often in teens and adults.

Depression with suicidal thinking and/or behavior is also now understood to be more common among those with mild ASD than among other people. It has been recommended that Primary Care Physicians (PCPs) consider screening patients with ASD beginning at age 11 for Depression and Suicidality on well care visits.

Some questions to consider in assessing risk for suicide:

- Is the person verbalizing suicidal thoughts or intent?

- Is there evidence of suicidal behaviors, poor judgment or mental illness?

- Is there a history of suicidal or para-suicidal behavior?

- Is the person unable to identify reasons to keep on living?

- Is the person engaging in, or is there evidence of, self-harm?

- Is the person verbalizing intent to self-harm?

- Does the person have a history of self-harm?

- Is the person unable to care for self?

- Is the person unwilling to accept support from others?

- Is there evidence of neglect and behaviors that put the person at risk?

Whether the crisis is spurred by aggressive/agitated behavior, or where nonviolent behavior results in the patient's self-harm, the first steps in the assessment will be to

- Evaluate the severity of the episode and the safety of the patient, and when appropriate, of the caregivers

- Identify and rule out potential medical drivers of the behavior, and depending on the symptoms, consider whether there might be a co-occurring mental disorder

- Using this episode as a template, develop a treatment plan and an emergency plan with the patient and caregiver(s).

When seeking external help in, or after, a crisis, here are some questions you will likely be asked. It might be helpful to consider your answers in doing your own assessment of whether this is a crisis.

- How often do these outbursts occur? How long do they last? What happens?

- What does the worst episode look like? What does the most minor episode look like?

- Does the person cause physical harm to others? How? Who are the targets? Parents, siblings, infants, pets? Is there property destruction? Is the person injuring him- or herself? How does he or she do it? Biting, hitting, head banging?

- What is the extent of those injuries to date?

- Are eyes being hit, windows/glass broken? Are ears being hit? How hard? Is there bruising?

- Is running away part of the episode? How often is this a component?

- How far from home has the person gone? Does the person respond to verbal directions to stop? Is there any running away not associated with an anger episode?

- Are there environmental hazards in the area—pools or bodies of water, busy streets?

Assessing severity and safety

- Remembering that aggressive outbursts are often "acute on chronic," what motivated the caregiver to seek help today, rather than before? What is the worst injury anyone has sustained?

- What is the worst damage the person has caused?

- If the person runs away (or otherwise leaves the area without permission or notification of others), have there been close calls or injuries?

What does the caregiver do?

- How does the caregiver handle this extreme behavior? What is the result? Are there others in the home who help?

- What does the caregiver do to redirect the person and end the outburst?

- Are restraints being employed? How are they done? Who does them? Does using restraints place the person or caregiver at risk for injury? Has the caregiver struck or otherwise physically injured the person?

What steps have been taken to improve safety of the environment?

- Does the home have door alarms and adequate door locks?

- Does the caregiver keep sharp objects and projectiles from key areas? If there is a yard, is it fenced?

- Are there other steps the caregiver has taken?

How is the caregiver's health and well-being?

- Does the caregiver have symptoms of Depression and/or Anxiety?

- Is he or she receiving treatment?

- What supports does he or she have for managing the person’s behaviors?

- Does he or she have access to respite?

- Does the caregiver show signs of suicidality?

- Passive suicidal thoughts (i.e. thoughts of not wanting to be alive) are common among highly stressed caregivers.

- Active suicidal thoughts (i.e. thoughts of taking one’s life) are rare, but should be assessed.

- Does the caregiver use substances? Which one(s)? How frequently? How much?

- There is emerging evidence that caregivers are at increased risk for Substance Use Disorder, especially in the context of a patient's extreme externalizing behaviors.

The person’s self-injury is getting progressively worse. Watch for:

Mental status changes following severe head banging

Eye injury, ear injury, dental injury

The person is at imminent risk for accidental injury or death

Running away

Drowning

Others may be injured by the person. Examples include:

An infant in highchair has been knocked over during explosive outburst

An older teenage patient who has grown quite strong hits his parent or caregiver.

There are other significant risks:

The parent or the parent/caregiver risks death by suicide

The caregiver may harm the person

The caregiver is impaired and unable to provide care

If You Suspect Abuse or Neglect

Unfortunately, people with I/DD have higher rates than the general population of being abused and/or neglected by caregivers or services providers in the home or other care setting. North Carolina law requires that anyone who suspects abuse, neglect, or exploitation of a child or disabled adult (age 18+) report it to the county department of social services in which the person with I/DD lives. A list of NC County Departments of Social Services can be found at https://www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/social-services/local-dss-directory. Ask for the Child or Adult Protective Services social worker.

Obtaining Emergency Care on Site

Does the family work with some type of behavioral health agency? Do they know the emergency plan with that agency? Do they know how to contact mobile crisis services for their area? Crisis services can be accessed via the LME/MCO for the county in which they live. See the link https://www.ncdhhs.gov/providers/lme-mco-directory for the contact information for them.

If the situation is unsafe and needs an immediate response, caregivers can call 911 as a last resort. It is also appropriate to call 911 if:

- There is a medical emergency

- The person needs to be evaluated for psychiatric hospitalization and they cannot be safely transported by a family member.

When calling 911, it is important for the caller to explain that the person has I/DD, and to request that a Crisis Intervention Trained (CIT) officer respond.

Using Emergency Services

Crisis services vary depending on where you live in the state but your Local Management Entity/Managed Care Organization (LME/MCO) can connect you to what is available. This could include:

- Mobile crisis services that can come to a home or other community location to help de-escalate the crisis

- NC Start offers crisis response, clinical consultation, training and respite for adults and children with I/DD. Please note that NC START for children is only available through your LME/MCO.

- Behavioral health urgent care centers provide immediate care to adults, adolescents or families in crisis. Care may include assessment and diagnosis for mental illness, substance use and intellectual and developmental disability issues, planning for referral for future treatment, medication management, outpatient treatment, and short-term follow up care.

- Child and adult facility-based crisis services provide an alternative to hospitalization for people in crisis who have a mental illness, substance use disorder or intellectual/developmental disability. Services are provided in a full-time residential facility.

Use of the Emergency Department (ED) is sometimes needed, however it should be used sparingly. It is the right immediate referral when the person’s safety is clearly compromised. Particularly when working with persons age 18 and older, be sure to check who the person’s legal guardian is. Adults with I/DD may be their own guardians, or others may fill that role. In the context of an adult who is his/her own legal guardian, a physician, eligible psychologist, or other specifically credentialed behavioral health professional in NC can initiate involuntary commitment if needed.

See https://www.ncdhhs.gov/assistance/mental-health-substance-abuse/involuntary-commitments for more detail about that process. You can also call your local magistrate for guidance if needed (open 24 hours a day). The magistrate for your county can be found by going to https://www.nccourts.gov/locations and selecting your county. Alternatively, if responsibility for guardianship of the adult with I/DD is with the county department of social services, then they should be notified https://www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/social-services/local-dss-directory.

In the extremely rare case where a legal guardian refuses to have the patient evaluated in the ED, after the need has been demonstrated, call 911 if harm is imminent, as well as child or adult protective services in the county department of social services. Here is an online directory for all the counties: https://www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/social-services/local-dss-directory.

Ideally, persons with I/DD and caregivers should be guided to the closest ED, but remember that some EDs have more experience and comfort than others serving people with I/DD. Do you know which one(s) in your area would be best?

People with I/DD and caregivers should understand that the ED is a good place to rule out medical factors for the crisis, maintain safety, and determine need for admission. That said, caregivers should also understand that most ED visits for explosive behavior will not result in psychiatric or other admission. In the rare cases when admission is necessary, people with I/DD and caregivers should understand that in the current resource climate, there will likely be significant time spent in the ED before admission, and in some situations, the psychiatric unit with an available bed may be some distance from the person’s home.

PREVENTION

- Identify triggers - To prevent a crisis we need to know the person’s triggers: What sets them off or makes them feel physically or psychologically unsafe? Then we develop strategies to avoid or defuse those triggers.

- Active listening and empathic responses

- We also need to build in strategies for the person to get more support—calling a trusted person, going for a walk, practicing the skills they have been working on.

INTERVENTIONS

During the intervention phase, we are working with someone who is dysregulated and/or engaging in unsafe behaviors. If you are on the scene, the safety of the person, others, and yourself are the most important factors. It can help to de-escalate if you:

- Avoid power struggles.

- Avoid phrases like “if you don’t do ____ , I’m going to call the police.” Offer choices instead. “Would you like to wait inside or outside?" or “Would you like to call your mom or should I call?”

- Watch your posture and body language.

- Uncross your arms, open your stance, and stand with one foot slightly behind the other.

- Avoid blocking exits.

- Make sure that the distressed person can leave the room without going through you if he or she needs to leave.

- Stay calm, neutral, and confident.

- Breathe.

- Talk softly but with confidence.

- Offer water or a snack. Many a crisis has been averted with good hydration and snacking.

- Ask for help.

- Ask the person who knows the child the best what will help the him or her calm down.

- Use community crisis services if needed.

- If these de-escalation techniques don’t work, call your Local Management Entity/Managed Care Organization (LME/MCO). These lines are answered 24 hours a day, and they can inform you of options for crisis services. You do not need to have a certain kind of insurance to receive crisis services through the local MCO— anyone in their area can receive crisis services.

If the situation is unsafe, call 911 as your last resort. You would also call 911 if there is a medical emergency, if law enforcement is needed for safety, and/or If the person needs to be evaluated for psychiatric hospitalization and cannot be safely transported by a family member.

If you call 911, ask for a Crisis Intervention-Trained (CIT) officer. CIT officers have specialized training for managing psychiatric emergencies.

DEBRIEF

The last part of the crisis response is the debrief. In the debrief the team is reviewing the event to learn

- What could they have done to prevent this crisis?

- What could have worked better during the intervention phase?

Check on physical and psychological safety of the person, observers, and family.

Make adjustments to the crisis plan, or create one if one doesn’t exist to prevent future crises. In the crisis plan be sure to be as specific as possible regarding triggers, and what has worked and not worked for the individual during a crisis situation.

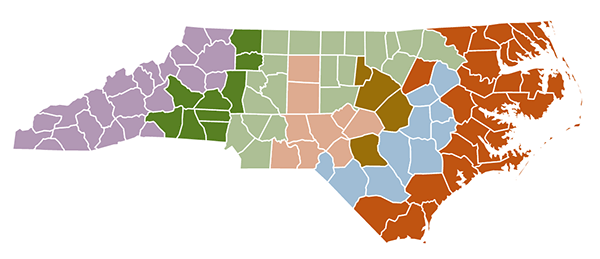

Accessing Crisis Services through the LME/MCOs

Many patients with I/DD use Medicaid for medical insurance. For their behavioral health care needs and emergencies, the Local Management Entity/Managed Care Organization is the point of contact for services. These organizations offer an access line answered twenty-four hours a day. Additionally, they can arrange an assessment if a child is between ages 5 to 21, has both mental health and I/DD needs, and is at risk of out-of-home placement or not being able to return from an out-of-home placement.

See the map below, and https://www.ncdhhs.gov/providers/lme-mco-directory for the contact information.

Local Management Entities/Managed Care Organizations Map (LME/MCOs)

Crisis Services

NC START (North Carolina Systemic, Therapeutic, Assessment, Resources, and Treatment) provides statewide community crisis support programs for people with I/DD and complex behavioral or mental health needs. Crisis prevention and intervention services are provided through crisis response, clinical consultation, training, and respite. There are three centers in the state that serve the west, piedmont, and east. Referrals for children (ages 6 and older) to NC START must come through the LME/MCO, therefore parents/caregivers should consult with their LME/MCO if they are interested in a referral. Referrals for adults (age 18+) to NC START can be made directly to the NC START center. Consult their website for more information, https://www.centerforstartservices.org/locations/north-carolina.

- The majority of crises among people with I/DD relate to aggression, explosivity, and anxiety. They are very often "acute on chronic" episodes.

- Assess the medical and physical drivers of irritability, and treat those when possible. Don’t forget that psychiatric medications could be part of the problem.

- Parents/caregiver(s) should work with medical and behavioral health professionals to plan for future crises. Individuals should be connected to appropriate resources—the LME/MCO, which is the gateway to many other services including mobile crisis response teams, and to NC START.

- Pay attention to the health and stress level of yourself as a family caregiver, and ask for help and/or respite.

- Use 911 and the emergency department sparingly but when the person’s safety is clearly compromised.

- Because people with I/DD are at greater risk than the general population, watch for crises without explosive behavior that may be symptoms of such psychiatric conditions as Depression, Psychotic Spectrum Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, Anxiety, and Suicidality.